|

The

Forms of Isshinryu

(And

some reflections on Steve Armstrong, who passed away

November 15, 2006)

Walk with me a bit, down the corridors

of time, to an era when American Karate was in its

infancy. Back then, I lived in Philadelphia. It was the

60's, and martial arts was something occasionally

portrayed in comic book ads (Are you old enough to

remember Count Dante?), but not found in the everyday

world. This was before Bruce Lee, and Chuck Norris, and

even before Five Fingers of Death appeared on

the horizon as the first major release of a true martial

arts film. It wasn't available, didn't exist, and if you

were lucky enough to find a dojo, you'd have to eat dirt

to get in. Walk with me a bit, down the corridors

of time, to an era when American Karate was in its

infancy. Back then, I lived in Philadelphia. It was the

60's, and martial arts was something occasionally

portrayed in comic book ads (Are you old enough to

remember Count Dante?), but not found in the everyday

world. This was before Bruce Lee, and Chuck Norris, and

even before Five Fingers of Death appeared on

the horizon as the first major release of a true martial

arts film. It wasn't available, didn't exist, and if you

were lucky enough to find a dojo, you'd have to eat dirt

to get in.

I knew of only one school

in all of Philadelphia back then. It was a traditional

Japanese school (I now believe it was a Shotokan

academy), and the workout floor was hardwood, finely

polished, class impeccably clad in white Gi's, and a

Sensei right out of my imagination. Of course, it was in

a part of town prohibitive for me to enter, and frankly,

the severity of the program was, by my measure, beyond

what I could endure.

|

|

|

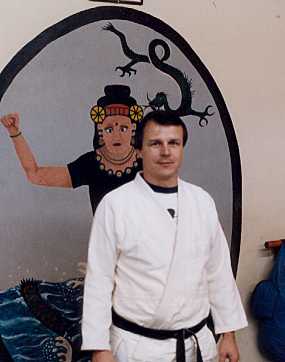

The

Armstrong Dojo, facing the Mizugami

|

|

In many ways, those days

seem like a distant dream. There were no videos, and

television was still in its infancy...strictly Jackie

Gleason, Milton Bearle, Ed Sullivan, etc. However, my

interest stuck, and I searched everywhere for anything I

could find on the arts. I remember my first big "hit"

was a bookstore off of Roosevelt Blvd. and Cottman,

where one afternoon, I struck gold. On the sports

bookshelf was a book by Gichin Funakoshi (Karate Do

Kyohan), which, when I inspected it, looked to be the

outline of a complete system. It took several weeks for

me to earn the $17.00 (back then, a considerable sum for

a book), but eventually I bought it, and with the

Master's guiding hand, launched my study of Karate. The

same bookshelf later contained works on a style called

Isshinryu, written by a Steve Armstrong. Reading and

thumbing through them, I saw they were a detailed

explanation of Isshinryu Kata, or forms, written by this

Armstrong, who had apparently studied the art while

stationed on Okinawa. I never imagined an American would

be so knowledgeable as to be able to produce his own

textbook, and the name “Armstrong” stuck. Someday, fate

permitting, I would seize the opportunity to meet this

Armstrong, and hear in his own words, how he had come to

learn Karate and propagate it in America.

|

|

|

The

Family Tree of American Isshinryu

|

|

Aside from that, there was

nothing. I learned what I could from Master Funakoshi's

book, and ultimately was blessed to find a true Shotokan

instructor in St. Louis, who filled in what was missing

from my training regimen. I had been in Shotokan for

several years, when a new art began to make inroads, Tae

Kwon Do. Who would have thought that within several

years, Tae Kwon Do would become a universal entity, and

Shotokan, with its rigorous training and demands for

perfect execution, would gradually fade to the

background. It was the late 60's and there were whispers

of a West Coast phenomenon named Bruce Lee. I attended

St. Louis University and experienced my first Karate

tournament (In those days, there might be one, possibly

two, during the course of a year). Sensei Steve

Armstrong was now bigger than ever, with his Seattle

Open getting national recognition. Tacoma, Washington,

where he housed his school, was to some of us in the

outlands a Mecca of inspiration. Of course, I don't mean

to slight the other "greats" by failing to mention them

here. The point is American Karate was in its infancy,

and my path is singular. There was Ed Parker, Joe Lewis,

Chuck Norris's star was on the ascendant, Mr. Cho in New

York, Sensei Don Nagle in New Jersey, Harold Mitchum,

Sensei Long, Fred Hamilton, Slocum and Pierce of New

York, Keehan of Chicago (before he became Count Dante),

and many more. These gentleman were pioneers, and to a

person, were deadly serious about what they taught.

Their skills were generally hard earned, learned well,

and taught well. Martial Arts became their lives, and in

many instances, their sole source of income and

inspiration. Still, even in the late 60's, schools and

instructors were scarce, and one had to exert

considerable effort to find a receptive school.

Tournaments were sometimes months and thousands of miles

apart, and required genuine sacrifice to attend.

Doubtless you're too young to recall, but it was before

the deregulation of Airlines, and a typical cross

country flight would cost the equivalent of a month's

wages. Some of the warriors back then were true ronin,

carrying blankets on their shoulders (there were no back

packs like today's, and no such thing as a day pack) and

spending nights under bridges or on the roadside. At

about that time, the Long Beach Internationals (Ed

Parker's tournament) blossomed into the acknowledged

national championship event, and held that prestigious

position for nearly fifteen years. To give you an idea

about how small the entire scene was, Mr. Parker and

Steve Armstrong were mutually supportive friends, as

they were with many others, including Chuck Norris.

Bruce Lee was originally from Seattle (Armstrong's

sphere of influence), and it was Parker's Long Beach

Internationals where a young Bruce Lee gave a brief

demonstration which turned the entire American Martial

Arts scene on its ear. Living in St. Louis, I continued

my endeavors in Shotokan, but attempted to get other

exposure where I could...there was only Tae Kwon Do, and

believe it or not, back then, Tae Kwon Do forms still

echoed the forms outlined in Funakoshi's Karate Do

Kyohan (They have since been completely reworked, so as

to more effectively incorporate the traditional Korean

Art of Taekyon into their presentation). It wasn't until

the late 60's that the door opened for learning the

Chinese arts. Earlier, I had lived with several Chinese

who were clearly quite skilled in traditional arts,

which they practiced diligently in their rooms, or in

private locations, beyond my scrutiny. When questioned,

they denied knowing anything, and never volunteered to

discuss. Thank goodness we're beyond that!

|

|

|

Recalling

the “old Days” with Sensei Armstrong

(circa 1993)

|

|

Well my story regarding

Mister Armstrong comes full circle. After St. Louis

University, I traveled back to New Jersey, then to

Philadelphia, and ultimately ended up in the Army,

relocated to Monterey, then to Southeast Asia. I

continued my personal pursuit of excellence in the arts,

and had opportunity to broaden my experience by

immersing into Hap Ki Do, Wing Chun, Arnis, Thai Boxing,

and Chinese sword. During my travels I worked personally

with several masters, and even learned Chinese Mandarin.

It wasn't until the mid seventies that I finally got to

Tacoma, WA. Actually, I returned to the states and was

stationed at Ft. Lewis, just outside Tacoma. It was

through a friend, Earl Squalls, that I had my first

opportunity to meet Sensei Armstrong.

On first contact, I was

blown away by his physical size. At the time, I

stood 6'3" tall, and usually weighed in at 225

lbs, yet I felt dwarfed by Mister Armstrong. This is

hard to explain, he wasn't much taller than I was, nor

did he weigh much more. It's just that everything about

him was big. His hands were huge, and all I could think

on first seeing those "paws" was he could kill me if he

ever hit me. They were nothing less than battering rams.

Master Armstrong was 44 years old and still in his

physical prime. He was pretty much held in awe by all

who knew him. Not just because of his imposing presence,

but because of his absolute command of Isshinryu, and

Karate in general. With a glance, he could discourse for

an hour on all the things he found in your Kata that

could be improved. His power was awesome, and one of his

typical "feats" was to throw a pine board in the air,

and "nail" it with a punch, while it was free floating.

The board would explode. If you think that's easy, try

it sometime. Few people talk about Mr. Armstrong's past,

but he was a bona fide war hero, having established

himself in the Korean War, and gaining enough notoriety

from his exploits that he became a member of President

Truman's personal guard before reaching the age of

twenty (yes, he enlisted underage). From the first

encounter to the very end, Armstrong emphasized that

meeting Tatsuo Shimabuku was the turning point of his

life. Master Shimabuku is known to us mostly through the

reflection of his art through generations of Isshinryu

students. Armstrong knew the man, and maintained

adamantly he never met a master who compared to

Shimabuku.

Imagine the diminutive

Shimabuku meeting Armstrong the first time, then

laughing when Armstrong said he was a Black Belt.

Shimabuku expected performance, and that remains the

tenet of Isshinryu to this day. Armstrong wanted to work

with Shimabuku, and indicated he already held Black Belt

status (nidan). Shimabuku asked Armstrong to

demonstrate, then laughed him off the floor. He did,

however, invite him to become a student. That began a

relationship that continued over the years until

ultimately, Master Shimabuku promoted Armstrong to 10th

dan (Donald Wasielewski attested to the existence of the

certificate, and also Mr. Armstrong's personal copy of

the Scroll of Kumite).

I eventually developed a

friendship with Armstrong. I was working Arnis with

Sensei Dave Bird, and had been accepted as a student by

Master Archibeque. That took most of my time.

Armstrong and I remained in contact for those several

years, having no clue about the evolving brain tumor

that was to derail his life in the martial arts on

September 8, 1977. That story is detailed in his

Isshinryu Karate.

His recovery from the

tumor removal was a nightmare, and it would not be

unkind to say he was never the same person again.

Certainly his awe inspiring persona remained, but his

physical prowess diminished, as did his ability to

remain physically active. Tragically, his judgment

clouded, and he alienated some of his most highly

regarded Black Belts, many of whom are established

Sensei even today. Without the fountainhead of Mr.

Armstrong's robust self, his influence in the world of

martial arts diminished (Did you know he was a member of

Elvis's Black Belt promotion panel?), and new voices

were on the horizon, eager to force retirement on

whoever remained of America's martial arts pioneers. We

had entered the era of protective equipment in

tournaments (Armstrong wouldn't allow it, always arguing

the best protective equipment was clean technique and

good control), widespread media attention, and the flood

of incoming styles, now in fact too numerous to even

mention. Where once, his was the only show in town, now

there were schools in every neighborhood. The dojo which

had once been filled to overflowing was now populated by

less than a handful of regular participants. Even within

his own style, there were challenges to his stature and

authority.

|

|

|

Sensei

Armstrong (Bill Mc Cabe (l), Don

Wasielewski (r))

|

|

Mr. Armstrong had always

been a proud, and headstrong man. Those were his great

attributes, but in the end, they precipitated his

ultimate slide into permanent retirement. Co-incident

with my meeting and befriending Mr. Armstrong, I became

best friends with Don Wasielewski. Per Armstrong, "Don

is the one person, the single person, that I would ever

ask to cover my back, and know it would be covered."

Wasielewski became one of Armstrong's students while

attending University of Puget Sound, where he was a 185

pound lineman on the football team. Armstrong's oft

cited expression that "It's not the size of the the dog

in the fight that's important, it's the size of the

fight in the dog" was inspired by his admiration for

Wasielewski. As fate would have it, I had the

opportunity to learn the Isshinryu system working under

Don, frequently at Master Armstrong's studio. In fact,

toward the end, we had the key to the location, and

reciprocating Master Armstrong's courtesy, allowed for

his senior students to participate in our sessions.

|

|

|

These

photos were taken at the time of

our last visit to Master

Armstrong’s school. We had

learned he decided to

retire. Concerned this would

be our last opportunity to

photograph the School’s Mizugami,

we took these final shots.

Within months, the building was

sold, and the school retired into

history.

|

|

|

|

After several years of

very hard work, Master Armstrong did return to some

level of stature in the martial arts world ("Seven times

you fall down, eight times you get up"). He had

opportunity to travel to Israel, and Europe, where he

authenticated and validated schools in several

countries. Sensei from some of those places came to

spend time with Armstrong, not infrequently staying, as

his guest, on the second floor of his dojo. I had the

good fortune of testing for Isshinryu Black Belt before

Mr. Armstrong on February 20, 1988. He was careful to

scrutinize everything I did, often asking for second

repetitions of my Kata, then offering extended

commentary into the Bunkai (combat applications), and

significance of the many moves. I experienced first hand

the passion he brought to the art, and his desire that

it be passed down, in tact. By decade’s end, Mr.

Armstrong began to backslide from the effects of his

illness. There were incidents between him and some of

his prominent students, who wished to have a degree of

autonomy, ultimately resulting in permanent breaks. His

classes diminished in number, and activity at the school

became marginal. He became forgetful, and heaven help

the soul who fell from his favor. There were some

incidents where lesser Black Belts either challenged

him, or intentionally provoked him. I remember one where

the unsuspecting challenger, positive that only a shell

of the former Armstrong remained, was dropped to

helplessness by a front kick that no one ever saw. The

late Earl Squalls (a tournament champion many times

over) commented afterwards the kick would have been

lightning fast for a person half Armstrong's size and

age, making the feat all the more remarkable. Tragically,

the regression continued. Mr. Armstrong slowly

lost the ability to control his emotional swings which

were becoming more pronounced, and even normal physical

activity was becoming a problem. He declared

his intent to retire, and over a short span of time,

liquidated his assets and resources in Tacoma and closed

his school. Among his final acts was the promotion

and designation of Sensei Donald Wasielewski to be his

successor in authority, and to whom, along with others

such as Master George Shin, he entrusted the

continuing heritage of Isshinryu in the Pacific

Northwest.

Not long after commencing

retirement, Master Armstrong’s continued deterioration

resulted in his care and ultimate residency at the

Washington Veterans Hospital where he passed away on

November 15, 2006.

He was

a pioneer, and made great personal sacrifices to

preserve and perpetuate his Master's art. Where

there was one, there are now many. Thank you

Master Armstrong.

So...dedicating this page to

my friend, and one of the great mentors of my life, I

would like to present the entire package of Kata from

the Isshinryu system. Details are provided

on each of the respective pages.

|