|

A Question of Balance Support this vessel with a donation, or itís into the briney deep we go (click the image now...before the tide washes you overboard)!!!

"Archie," as Master Archibeque prefers to be called, is the originator of many unique training techniques and philosophies, some of which have been previously shared with readers of Tae Kwon Do Times (Iron Fist Archie's Junky Fighting Tactics (November 1991); Iron Fist Archie's Exercise Junk (July 1987); Lesson of the Iron Cross (January 1991)). Updated versions of those articles can be found on this web site. Like all great Masters, Archie places particular emphasis on basics, in many instances, using mastery of basics to propel performance beyond the ordinary. Archie reminded balance is essential to every aspect of the martial arts. "Once a stance becomes fluid, it manifests as a body in harmony, or having balanced motion if you will. Power is delivered to the target only to the extent balance remains intact at moment and point of impact. A stance can be strong only if allied equally to strong balance." Archie remembered my early visits to his camp. Though I had already attained Black Belt status in other styles, I was unable to pass even his basic tests for balance. It was a sore memory and, for that reason, long since

forgotten. His words brought it all back. The

resurrected the image of several stakes mounted in the

ground with a 2"x4" board suspended edgewise between

them. While his students worked out, he challenged I

should walk the thin edge from one endpost to the other.

I appraised it to be a feat for circus performers and

let the challenge pass, thinking he wasn't serious. He

thereupon lined up his students and each traversed

without fail. When the last student crossed, Archie

pointed to me and ordered, "Now, your turn!" When class ended, I questioned Archie how I could master the skill. He responded balance was either there, or it was not. He stressed I should not think of it so much as a skill but rather re-discovery of a natural physical ability. He explained balance was related to mechanisms in the middle ear, which existed for everyone. When functioning normally, they would make the trip across the board an easy feat, even when the board was soft and spongy to my step. "How did I lose the ability?" "I'm not concerned with how you lost it. I'm concerned with whether you can get it back. Look at your lifestyle. Look at how you spend most of your time. Sitting at home, sitting at work, sitting at the TV, sitting in your car. It's a wonder your body even functions, considering all the time you've spent molding it into the shape of a seat." He invited me back promising to reveal "the secret." Of course, I accepted. The secret meant nothing

other than hard work. For several hours each class, I

stood at the exercise station attempting to cross over.

By week two, I had strung five steps together, without

falling. This increased slightly each passing week,

until eventually, I proudly succeeded in my first

crossing.

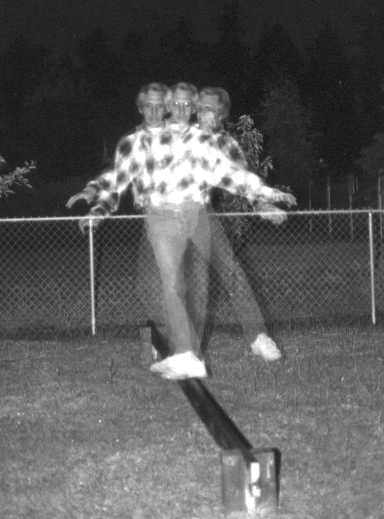

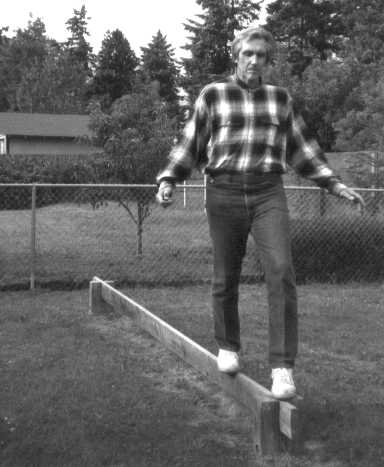

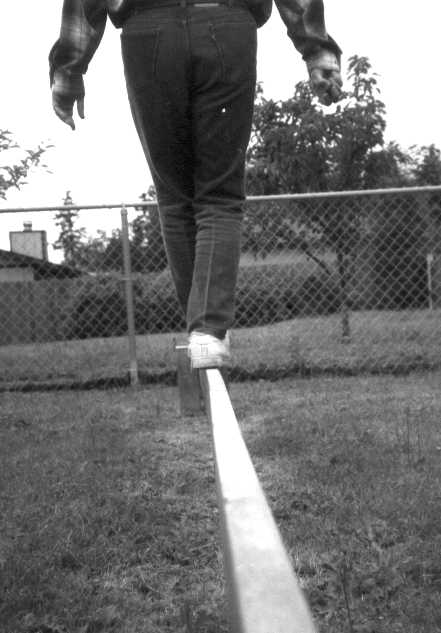

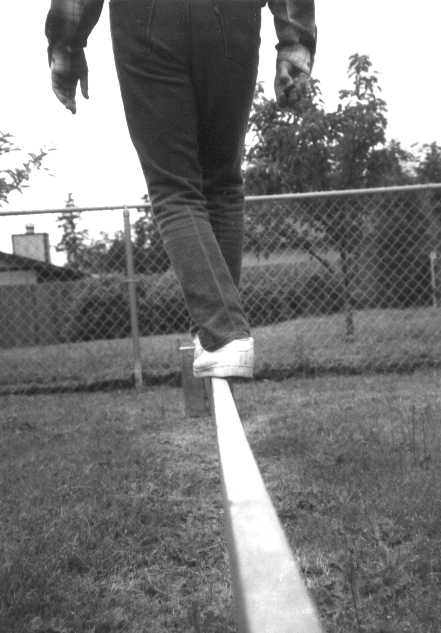

I was satisfied to end with that achievement, except Archie reprimanded I was only "beginning" with the lesson. He penciled a drawing and ordered I build a practice station in my yard, where I should work daily to perfect the requisite balance skills. His station is portrayed in photographs #1a-c, which demonstrate a 14' length of "2 x 6" board, mounted between 2 end-posts anchored in the ground. The end-posts are configured using adjacent "4 x 4" supports, mounted with a "2 x 4" as a spacer in between. In effect, the "2 x 6" bridge dovetails into the end-posts and can be replaced by a lighter ("2 x 4") board if one dares. The configuration in the

photographs takes approximately two hours to construct,

using materials costing less than $40.

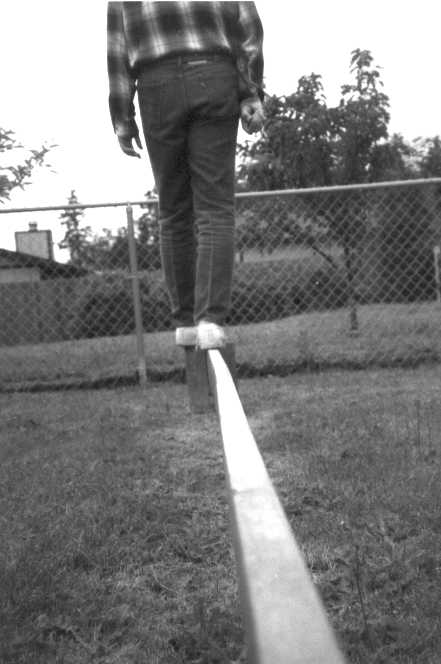

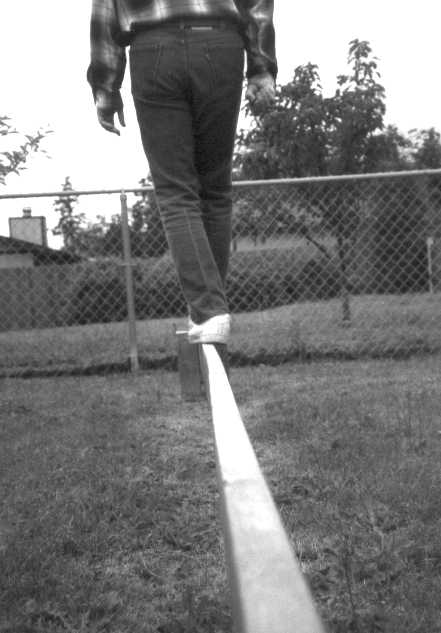

Archie stressed that with diligence, I should be able to cross the bridge, never falling. He urged I should practice in all weather, under all conditions -- wet, dry, icy, windy. It became something I could do at leisure (see photographic sequence #2a-g), almost a play activity. After several months, I met again with Archie and proudly demonstrated I could cross the bridge five times without falling or dismounting. It was then he said I was ready for Stage II, "walking backwards." He emphasized I should continue to expand my forward movement. By his reckoning, this meant being able to cross 50 times consecutively without losing balance. Concurrently, I should attempt to develop "walking backwards," in effect a new and separate balancing skill. As my skills crossing forward increased beyond my expectations, I struggled with the basics of crossing backward. Again months passed. Frustrated with my efforts, I called Archie for guidance. He stressed crossing backwards was simply walking backwards and that I should not think about the board or about technique. The only issue was balance and my focus on the task. Eventually, I made a successful backward crossing. With additional practice, I could cross consistently (see photographic sequence #3a-e). As was the case with all

he did, Archie had a clear standard to indicate when a

technique was mastered. I could now make the forward

crossing 50 times in succession and could cross

backwards several times each workout. He immediately

pronounced that I demonstrate 10 backward crossings

without losing balance. Only then would I be ready for

Stage III.

Two years into the practice, I met his second standard. Next, I was asked to cross to the mid-point of the bridge, turn 180 degrees and return to the post. Then, I crossed backward, turned 180 degrees around and continued forward. Finally, I was ordered to cross in darkness. Without light and vision, I was again a beginner, having to find new and deeper instincts to guide my crossing. Currently, I am years into the process. I expect Archie will continue to come up with new challenges for each new level, so I don't tell him where I'm at in my progress. When I first worked on these concepts, I sported a full head of black hair. As you can see in the photographs, that is no longer the case. In closing, I wish to share a few bonuses not promised when Archie first encouraged my work on balance. Not surprisingly, these drills have a clear meditative value. Early in my study, I abandoned other meditation exercises I had been practicing. Deeper focus and heightened awareness were immediate derivatives of the balance exercises and these carried over into all of my martial arts movement. Secondly, my skills in balance have continued to grow. Once, to my surprise and delight, I found a "2 x 6" wooden rail running approximately 100 yards around a high school parking lot. With glee, I attacked the challenge. As an added challenge, some of the support posts were loose and poorly anchored to the ground. As they oscillated, I instinctively adjusted, then proceeded to complete the entire circuit successfully. No sooner was that accomplished, then the voice of my mentor challenged within that I should be able to do it backwards, and then with multiple crossings. Before long, I was bringing my own students to the location as a test of their balance and focus. As I implied at the beginning of the article, Archie's chiding was warranted. In presenting some of the more esoteric aspects of his teachings, I overlooked that where he is most unique is in the emphasis on basics. I once had opportunity to demonstrate a complex form for a panel of masters, with Archie as a guest in attendance. I had prepared diligently for the exhibition and did well. The execution was superior, and the panel was duly impressed. Afterwards, as I chatted with my mentor in the corner, I worked to draw his praise and favorable comments, finally asking what he thought of my performance. He turned, nodded his head and said, "Good balance!" A high compliment indeed,

considering the source. |

[Home] [About Us

] [Archie] [Concepts] [Contact Us]

[Gun

Fu Manual] [Kata]

[Philosophy] [Sticks] [Stories] [Web

Store] [Terms of Use]

[Video]

Copyright 2000-2025, Mc Cabe and Associates, Tacoma, WA. All rights reserved. No part of this site can be used, published, copied or sold for any purpose, except as per Terms of Use .