|

Arnis and Better Hand Technique Support this vessel with a donation, or itís into the briney deep we go!!!

A

trained observer might observe that a competitor is

executing a form that has its origins in Northern China or

in a specific style, such as Hap Ki Do, Shotokan or Kenpo. A

trained observer might observe that a competitor is

executing a form that has its origins in Northern China or

in a specific style, such as Hap Ki Do, Shotokan or Kenpo.

Later in the day, you check out the Kumite (fighting competition). The differences that were so evident in forms competition are completely gone. If the fighters are wearing protective equipment, you'll note that after a short while each fighter starts looking like the next. It's clear something is happening here. Fighting under tournament rules has resulted in major dilution of the traditional fighting styles, producing a composite "style" common to the point fighting arena. Though instructors continue to debate the merits of tournament fighting, even the staunchest supporters of tournament competition agree that much of what constitutes the "pure", or "traditional" approach to the martial arts, has eroded in recent years. There are still instructors who can describe their early training as years spent mastering a handful of stances and techniques. The question that presents itself to the modern practitioner is, "Why is it that so few of the moves and stances found in traditional practice find their way into tournament fighting competition?" Instructors who have invested the years necessary to master Kata insist that each form is a "filing cabinet" for techniques originating during periods where all fighting, in the countryside or at the training hall was "for real." In that context, a missed block meant a slash from a sword or a bone crunching kick to the rib section. The masters of that era perfected the dynamics of power, movement, balance, timing and coordination. Mistakes meant defeat, injury and perhaps even loss of life. Realizing their "secrets" could be lost in the transmission from teacher to student, or during the course of time, these teachers "packaged" their knowledge into patterns or forms. If practiced with proper attitude, and indomitable spirit, these exercises guaranteed the dedicated student would be able to move freely, while maintaining knockdown power at all times. In an era where life and death confrontations are rare, and fighting is normally done under a tightly controlled protocol, how does the modern martial artist uncover the "secrets" of the masters? Should he or she commit himself or herself to a spartan program of forms practice? Would it benefit to find some partners who are willing to practice "no holds barred", and perfect their technique through "reality" training? Though some very fine practitioners have successfully adopted these paths, the vast majority of modern day students cannot make the commitment to practice forms for hours each day, or risk walking into the office with a broken nose or blackened eyes. The challenge for instructors today is to find new approaches which guarantee modern students will have the same level of fighting ability as their historical predecessors. One such approach is the incorporation of Arnis or Filipino stick fighting into the training format. A spokesman for this approach is Sensei David Bird of Tacoma, Washington. In addition to having mastered Arnis, Sensei Bird holds advanced dan rankings in Shotokan Karate, as well as Tae Kwon Do, and has also spent periods of time working with established Masters throughout the Pacific Northwest. Sensei Bird explained he had taught empty hand fighting for several years before he had opportunity to study Arnis with the late Cui Brocka, a Filipino master living in Tacoma. "I immediately noticed that my empty hand fighting began to have more of a flow. Things like joint locks, throws, trips or breaks which existed in theory but not in the practice of my empty hand fighting became an integral part of my arsenal." Enthusiastic about his discovery, Sensei Bird plunged into the study of Arnis and, after becoming certified as an instructor, incorporated it into the regular training program established for his students. "It's one thing training

for competition," explains Sensei Bird, "but quite

another thing to take the concepts or philosophical

foundation of a particular style and meld it into a

personal approach to self defense." Sensei Bird's

students begin class by working the empty hand

techniques. Once that is accomplished, they spend up to

an hour each class in Arnis training.

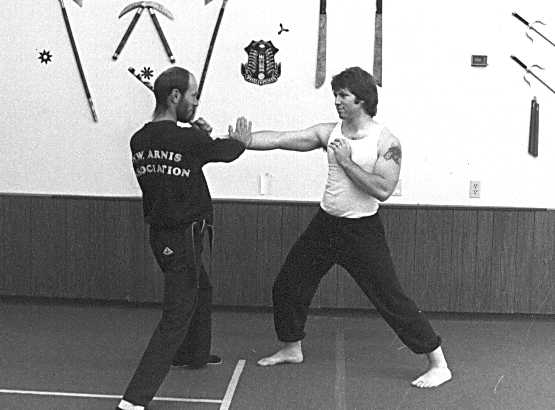

According to Sensei Bird, "We've all encountered trapping, blocking, parrying, sweeping and flow in our traditional training, but once people put on the fighting gear, where does it all go?" One of Bird's senior Arnis students observed that, "Concepts such as flow, joint locks, throws, trips and breaks have a place in real world fighting, but the only place most students are exposed to them is at the movies, where fighting scenes are carefully choreographed." Early in his

stickfighting training, Bird learned that trapping,

blocking, parrying, sweeping and flow are at the core of

Arnis. "The reason is simple. It doesn't work without

mastering those concepts and integrating them into your

movement. We're not playing tag out there. Being hit

with the stick means end of fight! Arnis means that when

your opponent attacks, you instantly neutralize the

threat, gain control of your opponent, then terminate

the encounter."

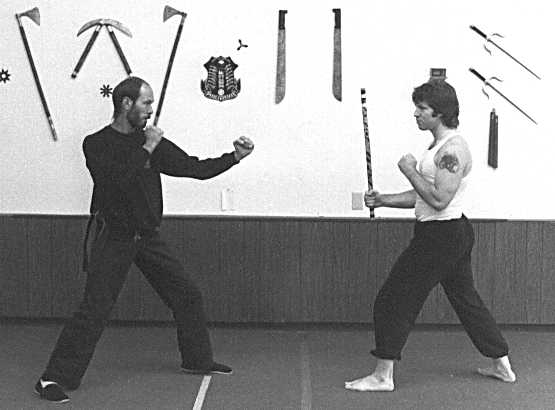

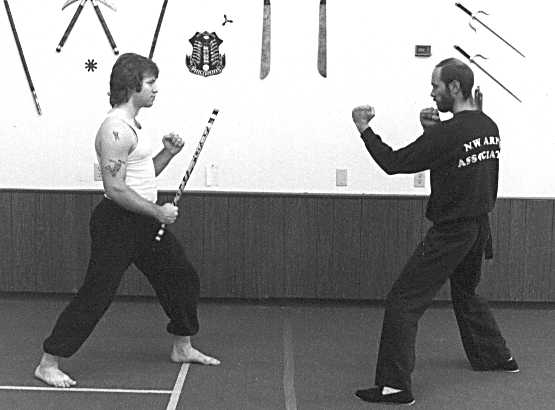

According to Bird, there

are many families of movement within Arnis. Foremost

among them are Solo Baston, incorporating one

stick while the empty hand parries and traps; Sinawali,

using two sticks in complex striking patterns; and Espada

y Daga, or sword and dagger. A beginning student

will learn basic striking patterns, appropriate parries

and the most efficient block for each strike. Though

there are no stances per se (the student is free to use

the foot positioning he or she is most accustomed to),

an integral part of early training is mastering flow.

Essentially, this means to always be moving away

from the opponent's power, and like a wave of water, to

engulf the opponent when he is fully extended. The

advanced disarms, come later, combining parries, traps

and sweeps in dynamic but efficient responses to

attacks. As one of Bird's Black Belt students relates,

"What can make this art difficult for some people is

that it's so direct and simple. Because of the way most

of us have trained, we've lost that simplicity and have

trained ourselves to always carry a lot of 'excess

baggage'. The principles of Arnis help the martial

artist to 'unload' and get back to the core of his or

her style, whatever that style is."

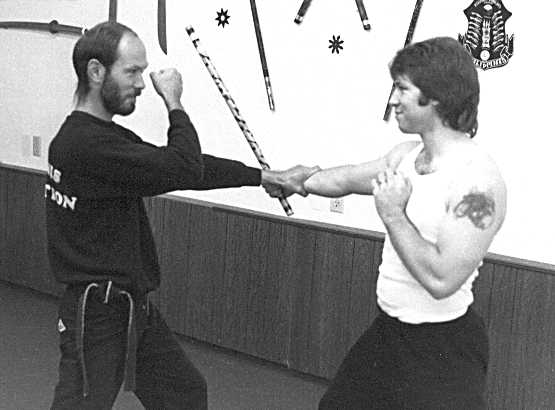

Once several months are

spent learning the basics of Arnis, students will learn

the empty hand responses to opponents armed with a

stick. "For the student interested in perfecting his own

fighting style, this is the icing on top of the cake. By

this point, the Arnis student has learned enough about

flow, trapping, parrying and redirecting the opponent's

force to incorporate these concepts into empty hand

responses to attacks, in essence effecting a bridge

between the study of Arnis and the martial artist's

native style."

It wasn't long before other martial artists and instructors took notice of what was happening at Bird's studio. Sensei Bird, realizing that training in Arnis could benefit his contemporaries as it had his own students, created the Northwest Arnis Association in August 1984. When this article was first published (September 1987), the organization numbered in excess of 200, representing a virtual cross-section of all martial arts. Sensei Bird conducts seminars at member schools, stressing low cost and bringing the knowledge to as many martial artists as possible. Once the techniques are presented and refined at seminar, they are practiced and further refined under the direction of the respective home school teacher, ensuring they are incorporated into the respective art. All involved testify the study of Arnis has brought deeper understanding to the core concepts of their own style. Cast your vote with a donation! WE NEED YOUR SUPPORT!!!

|

[Home] [About Us

] [Archie] [Concepts] [Contact Us]

[Gun

Fu Manual] [Kata]

[Philosophy] [Sticks] [Stories] [Web

Store] [Terms of Use]

[Video]

Copyright 2000-2025, Mc Cabe and Associates, Tacoma, WA. All rights reserved. No part of this site can be used, published, copied or sold for any purpose, except as per Terms of Use .

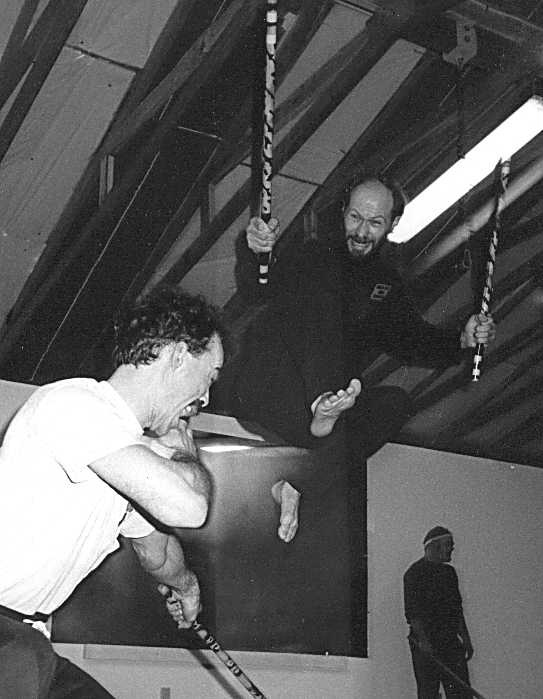

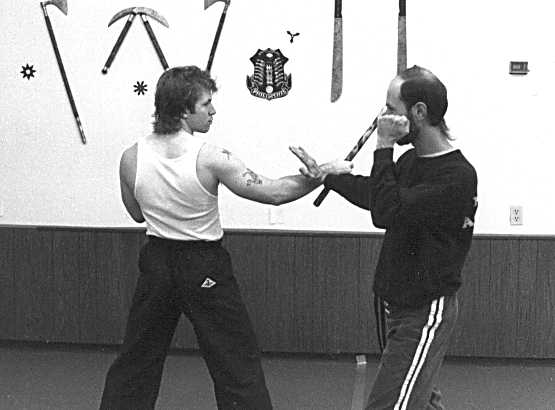

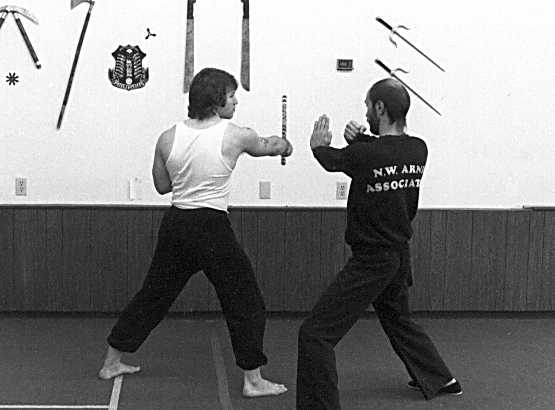

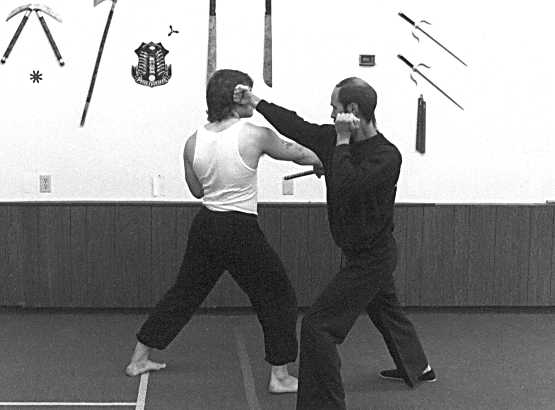

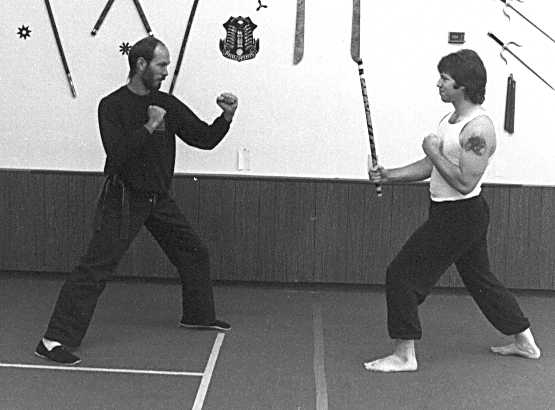

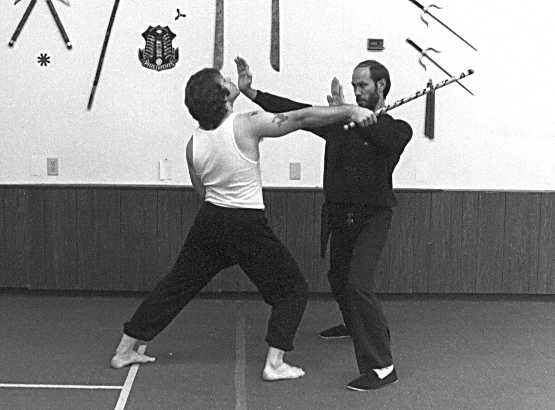

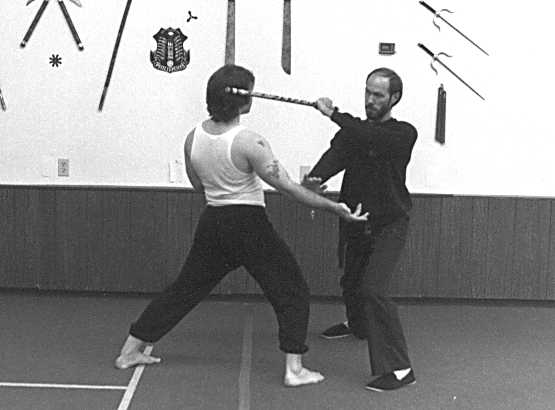

Sequence

#4: Executing a complex sequence,

Bird responds to a left temple strike by

simultaneously "checking" the attack and

stunning the opponent with a driving

upward palm to the head. As opponent

is being hit, Bird's left arm "snakes"

around opponent's right arm, "trapping"

the arm and weapon. A strike to

opponent's arm rips the weapon

loose. Bird lets the weapon drop

from under his arm into his left hand,

then strikes at opponent's head.

Sequence

#4: Executing a complex sequence,

Bird responds to a left temple strike by

simultaneously "checking" the attack and

stunning the opponent with a driving

upward palm to the head. As opponent

is being hit, Bird's left arm "snakes"

around opponent's right arm, "trapping"

the arm and weapon. A strike to

opponent's arm rips the weapon

loose. Bird lets the weapon drop

from under his arm into his left hand,

then strikes at opponent's head.